Tensions are running high in the Horn of Africa as Somalia continues to demand Ethiopia annuls a controversial port deal with the breakaway republic of Somaliland, or else withdraw its troops from Somali territory.

The biggest signal of Somalia’s displeasure with the Ethiopia-Somaliland deal was the signing on 14 August of a military pact with Egypt, Ethiopia’s biggest rival. Since then, Egypt has delivered two consignments of arms to Somalia including howitzers and armoured vehicles. There is also vague talk of Egypt deploying up to 10,000 troops to Somalia to help fight al-Shabab jihadists.

Increasingly isolated, Ethiopia has reacted to the deepening of ties between Somalia and Egypt with what critics say is nationalist sabre-rattling.

Last month, its prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, said anyone thinking of invading his country should “think 10 times” because “we Ethiopians know how to defend ourselves”, while his top general, Birhanu Jula, warned that “it seems history is repeating itself once again” – a reference to the 1977-78 war between Ethiopia and Somalia over disputed land.

“The leaders of Somalia have invited our historical enemy, forsaking the strong relationship and mutual cooperation it has established with Ethiopia,” said Birhanu.

Abiy’s quest for a Red Sea port is at the heart of this turbulence. Last year, he said Ethiopia’s landlocked status was a historic mistake that must be rectified – through negotiation or by force. On 1 January, he signed a surprise memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Somaliland, a self-governing territory that declared independence from Somalia three decades ago.

The deal sent shockwaves through the Horn of Africa and accelerated a diplomatic realignment that could impact the region’s geopolitics for decades. The details are a closely guarded secret, but Somaliland appeared to grant Ethiopia a lease on a 25-kilometre stretch of coastline to build a naval base in return for official recognition.

Somalia, which still claims sovereignty over Somaliland, has threatened war over the agreement, even though it has not yet seen the full text.

“In the international sphere, Somalia has very successfully cast Ethiopia as an outlier, a transgressor not abiding by international norms.”

Somalia has also launched a diplomatic offensive, rallying support for its cause. In addition to the pact with Egypt, Somalia has signed a deal with Türkiye to help it develop a navy, while Eritrea and Djibouti have expressed their support for Somalia in the dispute. So have the United States, the EU, and the Arab League.

In recent months, Somalia has expelled Ethiopia’s ambassador, accused its military of making “illegal” incursions across their shared border and claimed Ethiopia is smuggling arms into Somalia to help separatists and terrorists. Türkiye has twice tried to mediate between the two sides. A third round of talks was due to take place in Ankara on 17 September, but was postponed indefinitely.

“In the international sphere, Somalia has very successfully cast Ethiopia as an outlier, a transgressor not abiding by international norms,” said a Western foreign policy official. “There’s no doubt it has the moral high ground.”

Ethiopia has 3,000 troops stationed in Somalia as part of the African Union peacekeeping mission (ATMISS) fighting al-Shabab, which is due to be replaced by a new, smaller mission in January 2025. Another 5,000-7,000 Ethiopian soldiers are in the country under a separate bilateral agreement.

That makes Ethiopia the largest troop contributor in the fight against al-Shabab, ahead of Kenya, which has 4,000 soldiers in Somalia. Yet the future of Ethiopia’s deployments are now uncertain.

Somali National Security Adviser Hussein Sheikh Ali told The New Humanitarian that whether Ethiopian troops stay in Somalia “depends on how fast they get out of the MoU debacle”, adding that Ethiopia has “until sometime in October to renounce it”.

“We have tried to give them as much time as possible, but I think now it is getting closer and closer, time is ticking,” he said.

Referring to Ethiopian troops, Ali added: “Their presence is negative. The owners of this land now feel Ethiopia is an aggressor, not a partner.”

Enter Egypt

Ali downplayed the significance of the security pact with Egypt, casting it as similar to military support provided to Somalia by other partners such as the US, Türkiye, the EU and the Gulf states.

He also dismissed speculation that Egypt could deploy troops to Somalia as “rumours”, but suggested they could be part of the new AU force. “We have not yet decided who will participate,” he said. “This is a sovereign decision of Somalia.”

Nonetheless, Ethiopia is clearly rattled. In August, its foreign ministry claimed “the government of Somalia is colluding with external actors aiming to destabilise the region.” Last week, Ethiopian Foreign Minister Taye Atske-Selassie said the “supply of ammunition by external forces” could “end up in the hands of terrorists”.

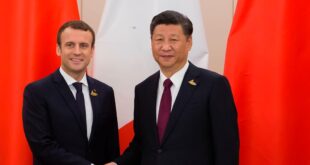

For its part, Egypt senses an opportunity to exert pressure on Ethiopia in the dispute over the Nile waters, which has dragged on for years. Ethiopia has continued to fill the reservoir of its Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) over the past four rainy seasons, despite loud protests from Egypt.

“Egypt is fed up with the lack of progress over the GERD. They’ve walked away from the negotiating table, so they’re using this dispute with Somalia to up the pressure on Ethiopia.”

Cairo sees the mega hydro-electric project as an existential threat to its drinking water, while Ethiopia says the project is vital to its economic development and argues it can benefit downstream countries by regulating the flow of the river.

Last year, after a meeting between Abiy and Egyptian President Abdul Fattah el-Sisi, the countries said they aimed to reach a deal within four months. The talks broke down, however, and the situation remains at an impasse.

“Egypt is fed up with the lack of progress over the GERD. They’ve walked away from the negotiating table, so they’re using this dispute with Somalia to up the pressure on Ethiopia,” said Ahmed Soliman, a researcher at Chatham House.

Alan Boswell, Horn of Africa director at the International Crisis Group, described the security pact between Somalia and Egypt as “part theatrical and part substantive”.

“I don’t think any of the military support for Somalia offered by Egypt is a game-changer yet,” said Boswell. “It’s signalling by Somalia to Ethiopia that it’s unhappy. But we could also start to see Egypt invest more in Somalia.”

For Somaliland President Muse Bihi Abdi, who faces elections in November, the MoU was a resounding diplomatic and domestic win. Western countries refuse to recognise Somaliland’s independence until African countries do so. The endorsement of Ethiopia, the most influential country in the Horn of Africa, would be a major first stepping stone towards achieving this.

Abdi is also facing rebellions in the east of Somaliland by clans who oppose the dominance of his Isaaq clan and favour rejoining with Somalia. The MoU helped undo some of the damage this instability has done to his reputation.

The risk of miscalculation

Although the risk of miscalculation is high, an interstate war is unlikely. Egypt faces crises in Gaza, Libya, and Sudan on its borders. It has little appetite for further conflict in the region. Ethiopia is still recovering from the 2020-2022 Tigray war and currently fighting several ethnic insurgencies. And Somalia’s army cannot even maintain domestic security, let alone launch an invasion.

Yet, in a region whose leaders have a history of using proxies to achieve their objectives, the dispute still has the potential to be destabilising. Somalia may up its support for proxies in Somaliland, while Ethiopia might ramp up its backing of militias in Somalia. Then there is the all-important fight against al-Shabab.

Despite coming under pressure in central Somalia, the jihadist group has successfully reversed gains by the Somalia National Army and launched several complex bombing missions against the capital, Mogadishu, and military bases.

Ethiopia has been fighting jihadists in Somalia since 2005. Its military has strong ties to the leaders of Somalia’s South West state and deep knowledge of local clan politics.

“If Somalia basically orders Ethiopia out of Somalia, that would be painful for both countries,” said Boswell from the International Crisis Group. “Egypt is in no way a substitute for Ethiopia. They probably wouldn’t deploy to the same areas, or possess the same expertise, if they deployed at all. Ethiopia has a lot of sway in the African Union, and there’s a big question mark over whether the AU would even approve Egypt as a troop contributing country in Somalia.”

Even if Somalia tells Ethiopia’s military to leave, it is unlikely to do so, said a Western diplomat. “It’s very possible Ethiopia won’t participate in the new AU mission, but they could stay on unilaterally or based on an agreement with South West State, where Ethiopian troops are the region’s security guarantee.”

Somalia is facing an internal constitutional crisis. Earlier this year, Puntland, the state neighbouring Somaliland, suspended its membership of the federation over a series of constitutional changes. If Somalia allows Somaliland to formalise its independence, this could precipitate a broader fragmentation of the country. Mogadishu therefore felt its only option was to take a hardline on the port deal.

For Ethiopia, gaining access to the sea is a matter of national survival. The port deal with Somliland should be understood in this way, “as a fundamentally national security action, a way of escaping a perceived encirclement by hostile states, not an economic deal”, said an Ethiopian researcher, who requested anonymity owing to the topic’s sensitivity. “Abiy sees this as his historical legacy, giving Ethiopia access to the Red Sea.”

Abiy’s foreign policy towards his Red Sea neighbours has been described as chaotic. Ethiopia has certainly found itself increasingly isolated after signing the Somaliland port deal. But Abiy has succeeded in inserting the idea of Ethiopia gaining sea access into regional policy discussions, points out the researcher.

“In this sense, his strategy has worked,” they said. “He has completely changed how we talk about this issue, to his advantage. You could call that smart, you could call it dangerous, but already it’s a success.”

موقع وجه أفريقيا موقع وجه أفريقيا هو موقع مهتم بمتابعة التطورات في القارة الأفريقية

موقع وجه أفريقيا موقع وجه أفريقيا هو موقع مهتم بمتابعة التطورات في القارة الأفريقية