Sahar Ragab

After a two-week hiatus triggered by a crippling fuel shortage, schools and universities in the Malian capital of Bamako reopened today. The nationwide educational suspension was imposed in late October when a blockade on fuel imports severely disrupted transport and mobility of both students and staff.

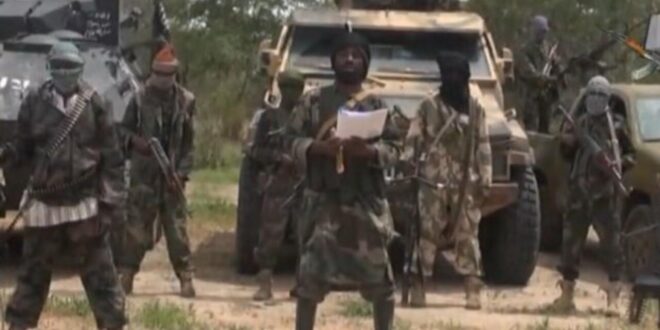

The fuel crisis stemmed from a blockade by the Jama’at Nusrat al‑Islam wal‑Muslimin (JNIM), an al-Qaeda-linked militant group, which targeted tanker convoys and fuel import routes from neighbouring countries.

According to the Malian Education Minister, Amadou Sy Savane, the disruption “affected the movement of school staff” and made it impossible to maintain classes.

With fuel supplies appearing to resume – some petrol stations in Bamako reopened as convoys arrived under military escort – the government set 10 November as the date for resumption of classes.

However, many remain cautious: long queues at petrol stations persist, and the supply remains far from stable. A parent in Bamako was quoted saying: “The children went to school this morning, but I remain concerned … many petrol stations are still closed.”

What this means for education:

The interruption comes at a critical time in the academic calendar, risking delays and learning losses.

The dependence of the education system on fuel and transport underscores vulnerabilities in Mali’s infrastructure.

While reopening is a positive step, the underlying logistical and security challenges remain acute.

Key questions ahead:

Can fuel supply remain sustained and secure, given the militants’ ongoing threats?

How quickly will the learning schedule recover momentum and bridge the gap left by the disruption؟

Will further disruptions force additional closures, undermining the stability of the school year?

In short: For now, classrooms are open again in Bamako—but the return to school is happening under shadow of a still-fragile fuel supply chain and broader security ris

موقع وجه أفريقيا موقع وجه أفريقيا هو موقع مهتم بمتابعة التطورات في القارة الأفريقية

موقع وجه أفريقيا موقع وجه أفريقيا هو موقع مهتم بمتابعة التطورات في القارة الأفريقية