Muhamad Yehia

Few American voters cite foreign policy as the deciding factor in how they cast their ballot. Yet the U.S. president has more international sway than virtually any other individual — especially at a time of immense geopolitical volatility.

We spoke to Steven Erlanger, The Times’s chief diplomatic correspondent in Europe, about what’s at stake.

How are U.S. election watchers around the world feeling?

There’s this kind of fascination and almost fury, a feeling that so much of life or policy in Europe depends on voters in North Carolina and Georgia and Arizona — because the American president, in a way, is everybody’s president. It’s just too big and important and rich a country.

What’s the view from Europe, more generally?

Western Europe, for the most part, is really nervous. In general, Western Europeans have always loved Democrats and disliked Republicans, going way back beyond Reagan. In Eastern Europe, where Ukraine is such a big issue, they are also nervous.

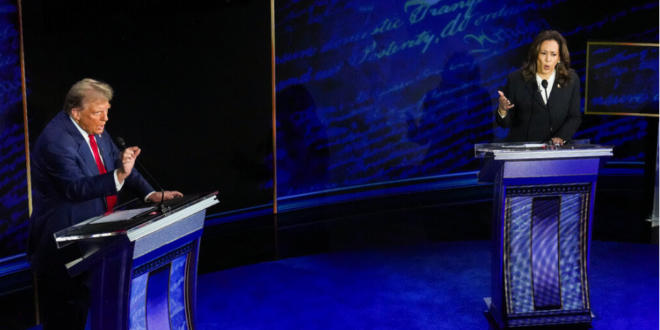

But some more far-right or hard-right leaders see Trump as something of a standard-bearer, and they share some of what seem like his biggest concerns: migration, abortion, gender, the loss of national identity. It’s important to say not everybody thinks Kamala Harris is God’s gift to democracy and to the world.

Harris has taken great steps to differentiate herself from President Biden. How might her administration differ?

Her whole experience and personal life is different — coming from California, being half Indian, half Jamaican. The cliché is that Biden is America’s last true trans-Atlanticist. That’s not really true, but it’s not in her experience. World War II was a long time ago, so her view is just going to be different.

One has the sense on Gaza, for instance, that Harris has more empathy with Palestinian suffering than Biden seems to have. Does she share the same commitment to Israel? Probably, but differently. Would she behave differently with Netanyahu? Probably. When it comes to her foreign policy, we really don’t know.

Would a second Trump administration substantially differ from the first?

Last time, Donald Trump wasn’t prepared to win, and he pulled together all these people he didn’t really know, most of whom were classic Republican and military people who spent most of their time trying to convince him not to do what he wanted to do.

This time, if he wins, he’s going to be surrounded by a lot of very smart, much more ideological people, who know how the system works, and who want to turn his instincts into policy.

What other issues are people particularly concerned about?

The biggest issue is national security, which is for Europe, really, Ukraine and NATO. The two are connected. There is anxiety over Trump, because he is, on many issues, rhetorically firm, but actually unpredictable. He thinks that NATO is a club that people have to pay dues to, and nobody’s paying enough — and America’s being the chump.

Some worry that if Trump, for example, starts saying he doesn’t believe in NATO, or won’t defend a member that isn’t spending enough on defense, he’ll undermine NATO’s credibility and the faith in Article 5. That flows into the next real worry, which is Ukraine. If Ukraine falls, Russia’s on the Polish border.

There is a related concern that if Republicans sweep the presidency and Congress there will be fewer restraints on Trump.

موقع وجه أفريقيا موقع وجه أفريقيا هو موقع مهتم بمتابعة التطورات في القارة الأفريقية

موقع وجه أفريقيا موقع وجه أفريقيا هو موقع مهتم بمتابعة التطورات في القارة الأفريقية