Ukraine draws focus away from Africa’s conflict hotspots, a key concern at the AU and UN Joint Strategic Assessment on Security in the Sahel high-level consultation.

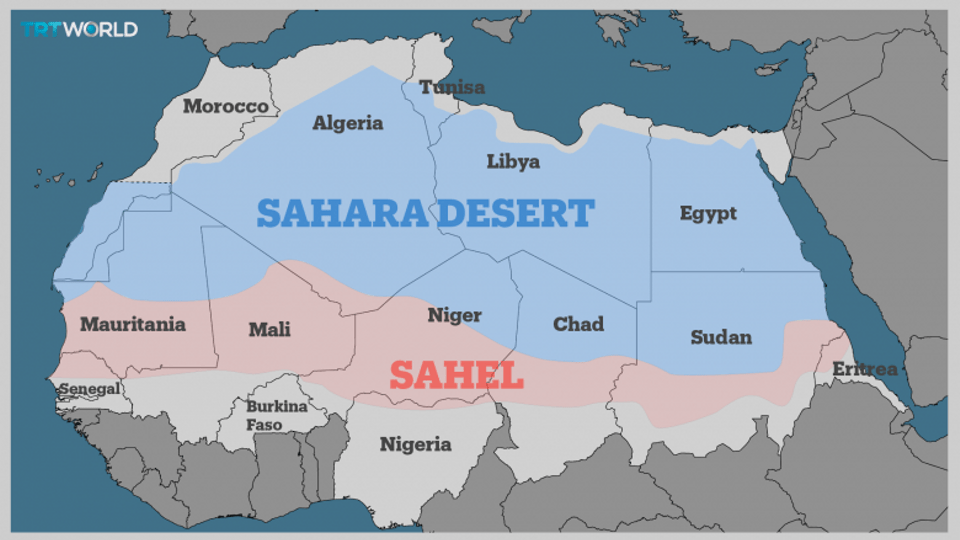

This meeting comes at a watershed moment, following President Macron’s announcement that the French are pulling their troops out of Mali. This follows a spate of coups in this region, successful in Burkina Faso, Chad, Guinea, Mali, and Sudan, unsuccessful in Guinea Bissau and Niger.

However well-trained by the West some of these soldiers are, some are developing a putschist appetite. This has resulted in a moment of increasing self-doubt among some of the key Minusma – the United Nations (UN) Mali peacekeeping mission – contributors who are reviewing their options on how to respond to a widening Sahel crisis at a time that they are also having to forensically focus on Ukraine.

Sahel-EU/UK relations

In Brussels, the Sahel and its adjoining coastal states are seen as an extended neighbourhood, important for collective security, but also for trade and the origin of a significant diaspora living in Europe.

The ongoing fractious diplomatic relations between Bamako and Paris currently represents danger and opportunity

Africa’s gold mining industry – traditionally dominated by South Africa – has shifted focus in recent years to Ghana, Mali and Burkina Faso, collectively producing over 275 tonnes; Guinea has the largest bauxite reserves in the world and Niger provides five per cent of global uranium production.

Add to this the growth of jihadist groups affiliated to Islamic State or Al Qaeda in states such as Mali and Burkina Faso which are increasingly unable to provide security guarantees beyond enclaves, and the strategic importance of this region is evident. It is a region the world ignores at its peril.

The result is a partial retreat of Western engagement in the region although, just prior to the EU-AU Summit, the EU’s foreign affairs and security policy chief Josep Borrell tried to reassure by saying: ‘We are not abandoning the Sahel. We are just restructuring our presence’.

The UK has slashed its overseas development aid to Niger by 50 per cent and, in January, UK Foreign Secretary Liz Truss quietly reviewed the UK’s 250-troop contribution to Minusma, reluctantly accepting it should stay for now.

Minusma’s future mandate is up for review before the UN Security Council this June, and African regional powers and France are also busy lobbying for its continuation and is encouraging Berlin, London, and others to remain engaged.

Some of the coping mechanisms which served communities well in the past have not been able to cope with the increased demographic and climate stresses of erratic rainfall and desertification that are quickening

The ongoing fractious diplomatic relations between Bamako and Paris currently represents danger and opportunity. The danger is geopolitics, illustrated best by Russia scaling up its engagement with Mali’s junta – such as deploying its Wagner mercenaries and claiming they will be more effective than the Takuba – and the taskforce of EU special forces supporting France’s Operation Barkhane mission.

The opportunity is that the junta, squeezed by Western and regional sanctions and with Russia now much distracted by its invasion in Ukraine, will need to compromise by seeking dialogue with the jihadists.

This could not have worked while the French were present in force, so exploring the possibility for an internal Malian settlement is worth encouraging. A new French security configuration in West Africa will see troop levels halved to 2,500 by the summer with an increased footprint in Niger and Côte d’Ivoire and with a greater focus on ensuring the security of coastal states that have seen a small number of jihadi attacks or attempted attacks as seen over the last couple of years in Togo, Benin and Ghana.

Have security operations succeeded?

There is no quick fix for stabilizing Mali or broader insecurity in the Sahel. France’s deep military engagement since 2013 has proved that a security strategy focused on countering violent extremism and stopping external migration to Europe does not work.

France’s Operation Serval was widely welcomed in Mali and the region at the time as successfully stopping the capture of the Malian state by jihadists. Its successor, Operation Barkhane from 2014, was also welcomed but its effectiveness was increasingly questioned in Mali and France and few tears will be shed at its ending in 2022.

France has also tried to prepare for its troop decline by encouraging a Mauritanian security initiative – the G5 Sahel. Made up of troops from Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger this has had limited operational effectiveness, especially as it excluded Senegal and key anglophone countries.

Its difficulties in the ‘three-border region’ where Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali converge and militant activity is at its most intense is a reminder of its limitations.

The G5 Sahel was partly created because although the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) still provides relevant legal instruments, it has failed to be a deterrent for further coups and its military and intelligence capabilities are struggling. Additionally, the key Sahelian state Mauritania is not a member.

The AU has also struggled which is worrying, as an effective regional economic community (REC) response was a key pillar for the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) unveiled in 2002 as a long-term structural response to the peace and security challenges on the African continent.

After a military coup in Niger in 2010, ECOWAS was instrumental in paving the way for the elections in 2011 which made Mahamadou Issoufou president. The first peaceful transition of power by elected presidents occurred in early 2021 when Issoufou stepped down having completed his second term. Possibly the transition process in Chad, following the death in armed action of President Idriss Deby in April 2021, might with AU encouragement follow a similar path.

What is needed?

Insecurity in the Sahel requires regular policy attention for the foreseeable future. This is a region of a handful of core flashpoints – the failed decolonization of Western Sahara, conflict in Libya, Lake Chad Basin/Mali overspill – feeding into communal and intercommunal violence, exasperated by increased ethnic identity politics and increasing contestation over land and water access.

Some of the coping mechanisms which served communities well in the past have not been able to cope with the increased demographic and climate stresses of erratic rainfall and desertification that are quickening. External securitization, whether by jihadists or foreign security actors such as the US, Europe, France, and now Russia adds complexity.

The three core crisis countries of the Sahel – Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger – all have roadmaps for effective decentralization which, if managed and resourced correctly could help gradually establish or re-establish some sense of positive state presence.

This would mean institution-building, better governance, and encouraging more accountable and developmental-focused governments, while also providing improved security – which is critical but past efforts have mostly failed, so security sector reform and military training need to have a much stronger focus on human security.

Dr Alex Vines OBE

Managing Director, Ethics, Risk and Resilience; Director, Africa Programme

موقع وجه أفريقيا موقع وجه أفريقيا هو موقع مهتم بمتابعة التطورات في القارة الأفريقية

موقع وجه أفريقيا موقع وجه أفريقيا هو موقع مهتم بمتابعة التطورات في القارة الأفريقية